This post has been translated from Dutch into English with DeepL. It will be manually edited and streamlined soon.

It is still early in the morning. In the distance, the sound of a locomotive coming on steam. The weather has suddenly cooled down after the oppressive heat of late summer. The smell of fog, coal, burlap sacks and rice.

I don't have to look for my black Fei He Flying Pigeon bike - I park it every afternoon or evening at the fixed spot I agreed with myself. Finding a black Fei He among a mass of other identical black Fei He's is not to be done, I concluded earlier this year.

My bag in the handlebar basket, bike unlocked, and on my way. There are not too many cars, all the more honking. Later, back in the Netherlands, the sound of a single horn brings me back to bicycles, autumn mornings and Hangzhou (read also Family #2). I blend into the stream of silent cyclists. First a stretch on the wide Huang Cheng Xi Lu, named after the city wall around the city that once stood here. Then turn right into the street that runs alongside the lake.

There are some small restaurants and modest shops where in early morning staff display their nemesis outside. Right along the street, on the pavement, quite a few bicycle mechanics are already waiting for patronage. A box of tools and some spare parts, a bicycle pump, that's all it is, but enough to fix the common bike repairs. The fog turns to patches here, between which a watery sun reports.

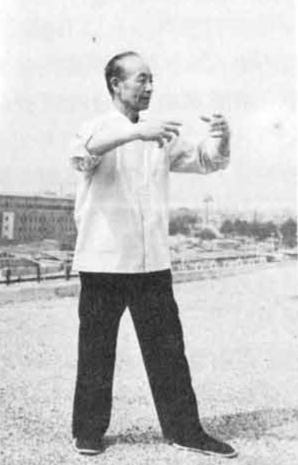

The road follows the shore of the Xi Hu, the famous West Lake. I cycle this road every working day of the week. My teacher in chi kung is called Luo Zhen and he runs a small training centre on the grounds of old Buddhist Ling Yin temple. To get there, I have to follow the northern shore of the lake, but halfway there I stop for a break.

An entrance gate, a ticket office, a small parking area for buses. Every day I pass by here, I see groups of Chinese visitors. They come for the grave and memorial of one of the historical national heroes, General Yu Fei. Could you compare him to Michiel de Ruyter, or Horatio Nelson? Over the centuries, Yu Fei's person became a model of incorruptibility; he is patriotism in person.

Yu Fei is born in 1103, during the Northern Song Dynasty. From the north, the Jurchen, invade the country and eventually the imperial court has to retreat to the south. There, the Southern Song Dynasty is founded, with Hangzhou as its capital. Yu Fei enlists in the army and quickly rises in rank. As commander, he leads campaigns against the Jurchen, who founded the Jin dynasty in the north.

Yu Fei is successful in defending the homeland, but at the court in Hangzhou not everyone is happy about it. There is a conspiracy against him and when he is called back to the capital, he is accused of high treason, imprisoned and eventually put to death. Soon after his death, he is rehabilitated and this temple on the shore of West Lake is erected to his memory.

The Southern Song will finally succumb. The Jin Dynasty of the Jurchen is overrun by another nomad-rider people, the Mongols. Led by their leader, Kublai Khan, a grandson of Dzhengis Khan, southern China is conquered as well. The Song Dynasty passes into the Mongol Yuan Dynasty.

During Kublai Khan's lifetime, a remarkable guest visited the ancient capital Hangzhou.

The second voyage again had Beijing as its starting point and followed the east coast southwards to Hangzhou (Quinsai), Fuzhou and Canton (Zaiton), South China's main port (Mangi). The northern part of the journey, crossing the Yellow River and following the Grand Canal to the Jangtsekiang, Marco Polo probably travelled more frequently. He reported that he had visited Hangzhou several times. Hangzhou was the former capital of the Southern Song dynasty, conquered by Kubai in 1276. With about 300,000 inhabitants, it was the largest city in the world in the 13th century. No other place gets as much attention in the book as Hangzhou and the neighbouring Western Lake. According to Marco Polo, the city is said to have a circumference of a hundred miles and contain 12,000 stone bridges. Wikipedia

Yu Fei not only goes down in history as one of the most skilled generals in Chinese history. He is also considered the founder of the Hsing I Chuan or Xing Yi Quan. This is considered one of the three Chinese internal martial traditions, alongside Tai Chi Chuan and Ba Gua Zhang. Yu Fei is said to have developed the Hsing I Chuan from various sources. As often happens in history, all kinds of things are not always rightly attributed to prominent historical figures and heroes. It is therefore up for debate whether the Hsing I Chuan tradition begins with Yu Fei.

The transmission of martial traditions generally took place without a written record. Knowledge and experience were passed on only within clans or families, or exceptionally to a confidant who had shown himself worthy of receiving the knowledge over a long period of time. Recording techniques and insights on paper certainly meant leaking vital information. Transmission took place in a practical and physical way, and was based on ingraining movement patterns through repetition. A theoretical foundation was in fact not an issue - or perhaps better said - theory was intertwined with physical practice.

We should also realise that the circles where the various martial disciplines circulated were generally illiterate. Only a small upper layer of Chinese society was proficient in the language, and that did not include the bulk of the military profession. During the 19th century, martial disciplines were recognised as valuable cultural and heritage in China. Doctors saw its value for preventive medicine. Political philosophers and activists saw its potential for education and strengthening discipline. For the first time, the techniques and history of the many martial disciplines were researched and described. However, many gaps remained in the knowledge of their genesis and lines of transmission. Legend and reality are often difficult to separate.

The fact is that a central training stance within Hsing I Chuan, the san ti shi - the triangle stance, may very well have had its origins in the use of stick and lance in Yu Fei's infantry. The 'open' san ti stance evolved over the centuries into the more 'closed' chen bao zhuang (read: tree time chi kung #3).

So let us assume that General Yu Fei was indeed at the root of Hsing I Chuan. For many centuries, there is no mention of it and it seems to have been lost. Until around the transition from Ming to Qing dynasty, a certain master Ji Ji-Ke, aka Ji Long-Feng, found a training manual by Yu Fei and gave Hsing I Chuan its current form. The style spread and one of the keepers of the tradition in the 19th century was Guo Yun-Shen. His disciple was Wang Xiang-Zhai and with him the I Chuan tradition begins with its range of standing training stances. Thus, according to this line of transmission, there is a direct connection between Yu Fei and the practice of standing chi kung.

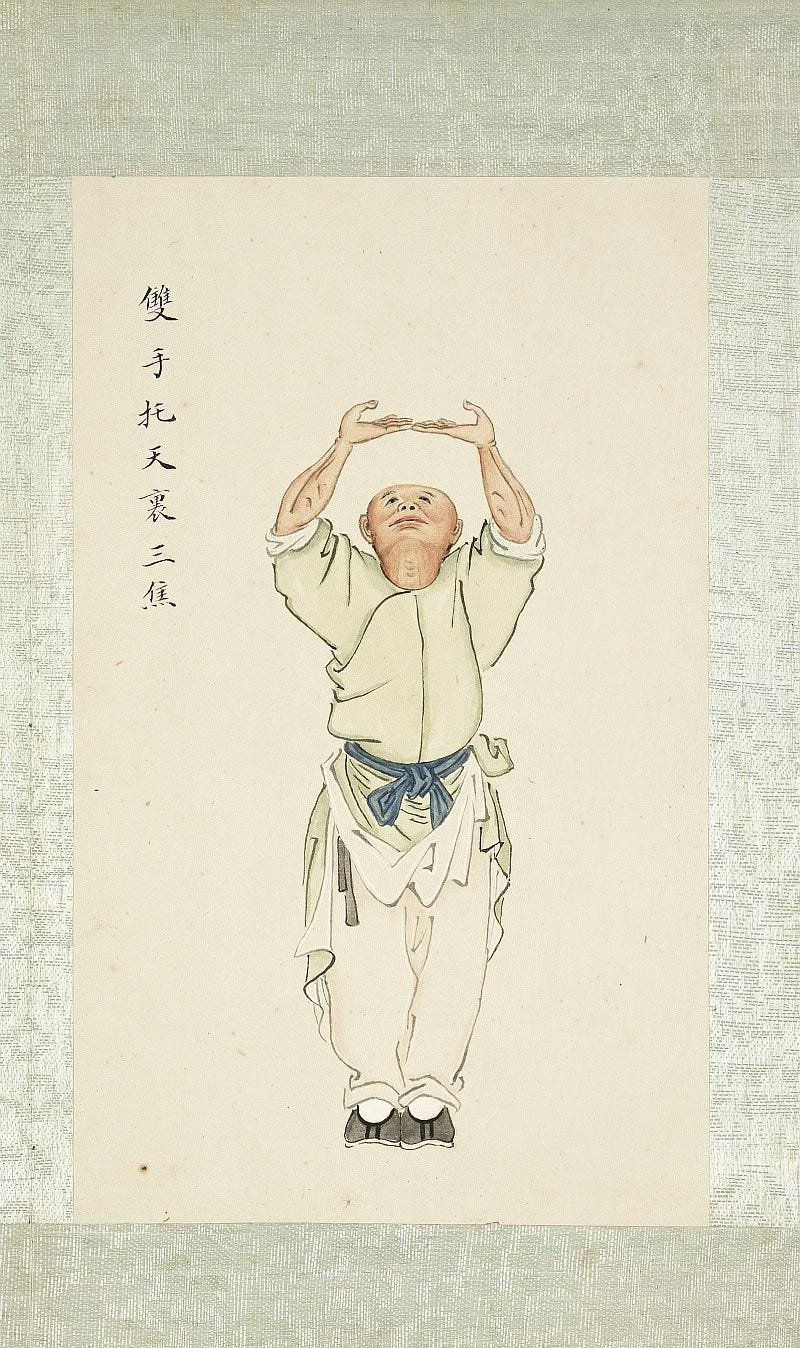

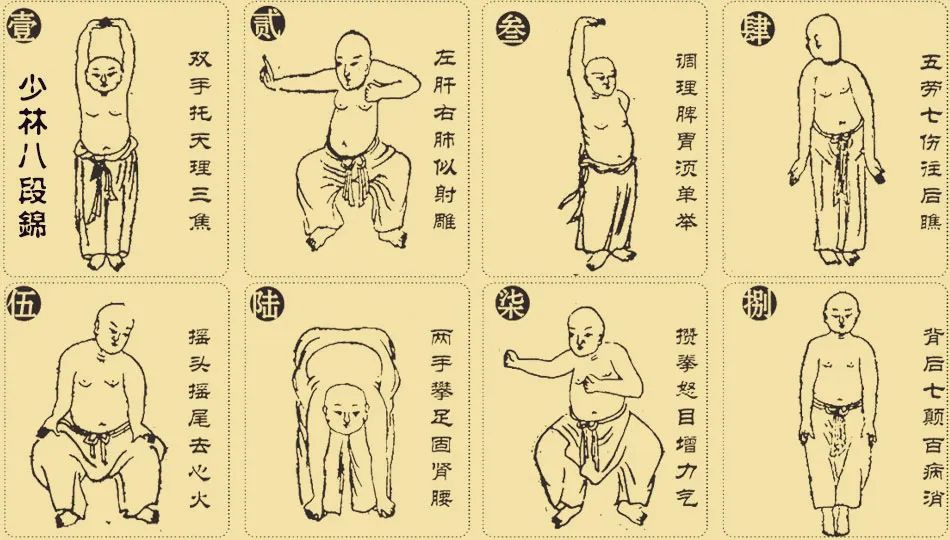

Another tradition with which Yu Fei is associated is the Ba Duan Jin, the Eight Brocade series. He is said to have designed and deployed this series of exercises for the physical and mental resilience of his soldiers. The exact form in which Ba Duan Jin was practised during Yu Fei's time is not known. Between the early 12th century and the present, Ba Duan Jin has seen many imitations and has evolved in numerous variations.

To be followed up soon ...