TAKING A POSITION HALFWAY

Tree Time Chi Kung #3 (en)

This is a sequel to:

This post has been translated from Dutch into English with DeepL. It will be manually edited and streamlined soon.

USELESS

Something we place little value on becomes a sideshow. What becomes an afterthought gets less attention. In the article 'Why rubbish collectors earn more than bankers', Rutger Bregman describes the huge impact of a strike by New York rubbish collectors in 1968 (Lees: Waarom vuilnismannen meer verdienen dan bankiers: Rutger Bregman in De Correspondent). By contrast, a strike by Irish bankers in 1970 is barely noticed. One would say that the - indispensable to the functioning of the city - rubbish collector would be a well-paid job, with status. What is expendable and what is indispensable? What is valuable and what is worthless? What useful and what useless?

I came to live in Amsterdam in the early 1980s. I remember quite a few places in and around the city, which were apparently not labelled as valuable. Where project development and market economy had not fully arrived. These urban frayed edges gave breathing space, room for creativity. For instance. the little land between Artis and the Entrepotdok, Zeeburg Island, and the no man's land that loomed up as soon as you passed under the railway viaduct on Czaar Peterstraat. They formed the city's in-between-space. Everything that lives needs such in-between-spaces. It comes in several guises: sleep, dream, boredom, recovery, creative vacuum, not to mention play. Anno 2021, in a city like Amsterdam, those useless places have almost all disappeared. And with them, less opportunity to get bored, to dream, recover, and thus come up with fundamentally new ideas.

The Taoist classic Zhuang Zi recounts the phenomenon of worth and worthless in four places, in the form of an encounter with a tree (Zhuang Zi, translation by Kristofer Schipper or by Burton Watson). First, Hui Zi tells of a tree that is totally unusable for the carpenter:

Its trunk is too gnarled and bumpy to apply a measuring line to, its branches too bent and twisty to match up to a compass or square. You could stand it by the road, and no carpenter would look at it twice. Your words, too, are big and useless, and so everyone alike spurns them!

A little further on in the book, master carpenter Shi and his apprentice walk past a giant oak tree on a journey.

It was broad enough to shelter several thousand oxen and measured a hundred spans around, towering above the hills. The lowest branches were eighty feet from the ground, and a dozen or so of them could have been made into boats. There were so many sightseers that the place looked like a fair, but the carpenter didn’t even glance around and went on his way without stopping. His apprentice stood staring for a long time and then ran after Carpenter Shi and said, ‘Since I first took up my ax and followed you, Master, I have never seen timber as beautiful as this. But you don’t even bother to look, and go right on without stopping. Why is that?’ ‘Forget it—say no more!’ said the carpenter. ‘t’s a worthless tree! Make boats out of it and they’d sink; make coffins and they’d rot in no time; make vessels and they’d break at once. Use it for doors and it would sweat sap like pine; use it for posts and the worms would eat them up. It’s not a timber tree—there’s nothing it can be used for. That’s how it got to be that old!’

That same night, the oak appears in the master's dream. The tree fulminates against him that usefulness only leads to abuse, exploitation and mutilation.

What are you comparing me with? Are you comparing me with those useful trees? The cherry apple, the pear, the orange, the citron, the rest of those fructiferous trees and shrubs—as soon as their fruit is ripe, they are torn apart and subjected to abuse. Their big limbs are broken off, their little limbs are yanked around. Their utility makes life miserable for them, and so they don’t get to finish out the years Heaven gave them but are cut off in mid-journey. They bring it on themselves—the pulling and tearing of the common mob. And it’s the same way with all other things.’

The Complete Works of Zhuangzi - translated by Burton Watson

Ziqi of Nanbo also spotted a giant tree during a walk …

… different from all the rest. A thousand teams of horses could have taken shelter under it, and its shade would have covered them all.

On closer inspection …

… he saw that the smaller limbs were gnarled and twisted, unfit for beams or rafters, and looking down, he saw that the trunk was pitted and rotten and could not be used for coffins.

And finally, Master Zhuang Zi himself comes on the scene. A woodcutter tells him that useless wood leads to a very elderly tree.

Zhuangzi said, ‘Because of its worthlessness, this tree is able to live out the years Heaven gave it. Down from the mountain, the Master stopped for a night at the house of an old friend. The friend, delighted, ordered his son to kill a goose and prepare it. One of the geese can cackle and the other can’t,’ said the son. ‘May I ask, please, which I should kill?’ ‘Kill the one that can’t cackle,’ said the host. The next day Zhuangzi’s disciples questioned him. ‘Yesterday there was a tree on the mountain that gets to live out the years Heaven gave it because of its worthlessness. Now there’s our host’s goose that gets killed because of its worthlessness. What position would you take in such a case, Master?’ Zhuangzi laughed and said, ‘I’d probably take a position halfway between worth and worthlessness. But halfway between worth and worthlessness, though it might seem to be a good place, really isn’t—you’ll never get away from trouble there…’

What a wonderful lesson in mental balance for the martial practitioner!

OPEN SPACE

Our daily lives are riven with utility. At the end of the line - concerning education, the economy, healthcare, etc - the bottom line is settled. It is about the net, and therefore about efficiency. Now, we have long known that far-reaching efficiency has vulnerable sides. If you have time, listen to the sharp observations in the podcast How our obsession with efficiency makes us vulnerable to unlikely dangers by Michiel de Hoog in De Correspondent. Efficiency does not just lead to uniformity. Space and time are bricked up. Efficiency does not tolerate loafing and daydreaming. No play and creative laziness, no true renewal and vital change.

Ten years ago, I joined the Cloud Appreciation Society. Membership has as few obligations as cloud observing is strenuous. Unlike collecting stamps or otherwise, clouds cannot be kept. Ownership of an everyday or unusual cloud formation is not possible. Nor is fixing these wondrous natural phenomena. Clouds are best observed from a lazy position, chair or hammock, walking, empty of ulterior motives. That kind of mindset is entirely consistent with that of the tai chi chuan and chi kung practitioner.

A willingness to invest in the useless, welcoming the creative vacuum. To value the seemingly worthless daydreaming, sleeping, playing around. The courage to invest in the opposites of focussed action and ambiition without end.

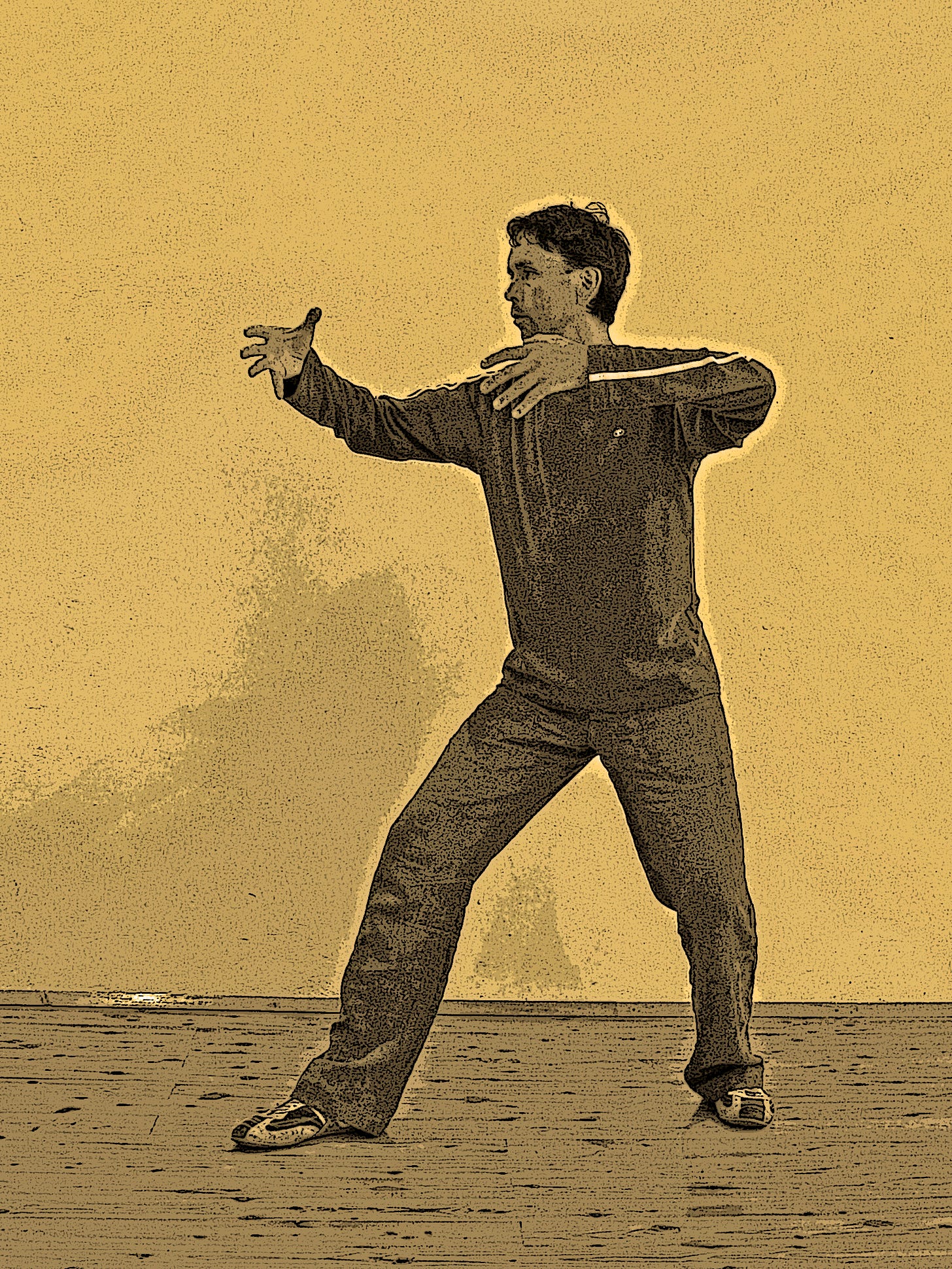

The most practised zhan zhuang posture has several names: ‘embrace a balloon’, ‘embrace a tree’, ‘three-circle posture’, or 'cheng bao zhuang' - 'support-embrace posture'. The ultimate feature of this training pose is the in-between-space. It is not the physical body that is in the spotlight, but the open space between the different parts of the body. Not the stiff material of the bicycle tyre, but the air inside gets the attention.

Stand at your favourite spot: home, balcony, park or somewhere in nature. Standig near a a tree offers a good role model. Feet parallel, knees slightly bent. Lower body following gravity. Experiencing a lift from the crown. The arms make an embracing gesture. The hands an encompassing gesture. Between the fingers is space, as in the palms. Between the arms is empty space. Under the chin likewise. Between the knees, and behind the knees. Experience room in front of the body, as well as that behind it. Like the fingers, the toes are relaxed and slightly spread. Experience room under the feet, following gravity, in the diection of the nadir. Likewise above the crown, in direction of the zenith.

Create room under the armpits, and also between the ribs. On either side of the body, there is the spaciousness of the round horizon. The more you practice this ‘cheng bao zhuang’, the clearer it will become that your intentioncan move in two directions at once. Balancing opposing movement is at the core of standing still. Two opposing intentional movements at once create volume. The volume of a balloon being inflated, of an expanding cumulus cloud, or that of the voluminous treetop, which you may have stood near. Experiencing the space that surrounds you, and experiencing the inner space of your body, are mirrors to each other.

The left elbow moves to the left, the right elbow to the right. That would result in a a separation of the arms. Therefore, the expanding intention in the arms is dynamically balanced by an intentional closing of the arms. A slight opening and closing simultanously, resulting in a still posture.

The eyes look forward and are inviting the whole body to lean towards a perceived future. That would ulimataly result in a forward fall or a forward step. Therefore, the intentional move forward is balanced by standing firmely on the heels, and comfortably sitting downward and leaning backwards. A future oriented intention is combined with a past oriented action, resulting in a still posture, with high internal dynamics.

In Walden, Henry David Thoreau describes the corporeal experience of time, the coming together of the dimensions of time and of space.

My days were not days of the week, bearing the stamp of any heathen deity, nor were they minced into hours and fretted by the ticking of a clock; for I lived like the Puri Indians, of whom it is said that "for yesterday, today, and tomorrow they have only one word, and they express the variety of meaning by pointing backward for yesterday forward for tomorrow, and overhead for the passing day.

In The Dynamics of Standing Still, I wrote about six directions of visual perception and imagination, in-between-space, and the time dimension. The image I included was a free-standing linden tree.

A CIRCLE

Young children have original mind. Show them a drawing of a tree: crown, trunk and roots. And ask them where the tree gets most of its nourishment from. Their answer will often be that the tree is nourished from the sky. I, being adult, with all formal training and study, would be tempted to answer, that the tree draws its food from the soil. Picture that: a forest giant standing in a crater, all its fertile soil eaten up! Of course, the tree grows from the sky.

What we animals exhale, plants breathe in. And what green life exhales is life-bringing oxygen for us animals. Nothing new under the sun, basic biology knowledge. Still, the breathing of an animal is described in another chapter, or in an entirely different book, as the breathing of the green plant. The interconnected breathing of plants and animals is the epitome of symbiosis. Plant breath and animal breath should be described in the same book, in the same sentence. Or drawn together in a simple infographic. A red haemoglobin plane and a green chlorophyll plane, in an ultimate taiji embrace. Two breaths contained in one circle. We owe our life to the green.

STANDING IN A TREE

Get up early and go to your neighbourhood park; go out to a place with a large mature tree. Maybe you are privileged to have your own garden, with a tree. Stand at ease next to the trees. Stand neutrally, with your arms along your body, in the wu chi pose of the first part of this article. Or in the posture described above with both palms on your stomach. Or in the cheng bao zhuang with both palms at chest level. Stand relaxed and unconcerned, so that you can observe and reflect freely.

I concluded the first part of this article by suggesting 'standing on a tree' as a possible translation of zhan zhuang. Instead of the usual 'standing like a tree'. The trees hidden half is underground and you stand atop of it. The horizontal circle circumferancing the extensive root system is twice, sometimes four times, the size of the circle around its crown. At the same time you are standing under the tree’s crown. Zhan zhuang can now be translated as 'standing in a tree'.

While optimising the space between your fingers, toes, arms, knees, armpits etc etc, stand in the open, empty space of the living tree. Enjoy your breathing. Where 'your' is not ment singular, but plural. The breathing of the tree and your bretathing as one inseparable entity.