AN INNER LANDSCAPE

Tree Time Chi Kung #2 (en)

This is a sequel to:

This post has been translated from Dutch into English with DeepL. It will be manually edited and streamlined soon.

AN UNKNOWN WORLD

For part of the year, I live with my family in a wooden cabin, in a forest along the Overijsselse Vecht. From the riverbank, the land is gently sloping, a remnant of sand carried over the centuries. Most of the oak trees around the house are relatively young, around 75 years old. Trees and the undergrowth are home to a wide variety of living things. A few years ago, on a spring morning, we counted no less than 30 species of birds within an hour. A considerable amount for a forest of that age.

But here the story takes an unexpected turn. This forest is a remnant of oak coppice culture. For centuries, logs were felled every so often in such groves. For construction timber, for posts and stems, as fuel for stoves and ovens. But the most common use of the coppice was in the tannin from the oak bark, used in tanning. (read: Eikenhakhout langs de Vecht: Ab Goutbeek) The trunks were cut some way above the ground. And from the remaining stubs new branches grew naturally. The forest floor itself remained untouched. An ecologist from the Landschap Overijssel estimated the 'age' of the forest floor at 600 years . For all those centuries, the soil remained free of spade and plough. The communal root system, the thick humus layer and a highly diverse soil life remained intact. There was no disturbance to the soil microbiome, the interplay of the myriad species of micro-organisms, and the invisible world of threads of fungi and moulds.

Many a bookshelf contains a tree and plant guide, and perhaps a booklet on local fauna. What shows itself to us above ground easily grabs our attention. And can be drawn out, photographed and described with ease. All plants, trees and larger animals have thus earned names and fame. But how different for everything that lives below the surface, hidden from our daily gaze. There will hardly ever be a booklet in that same cupboard, revealing the dark and unknown underground dimension of life. And explains the 'wood wide web', the intriguing forest internet. A communication network of fungal threads between root ends of trees and the earth, and between trees themselves (read: De Microbe Mens - Remco Kort. Also visit Micropia, the first and only zoo for micro-life!). Right under our feet and yet almost completely undiscovered.

AN INNER LANDSCAPE

Similar unimaginable biodiversity can be found even closer to home. Hundreds of different species of bacteria, as well as viruses, yeasts and fungi chose your gut as their habitat. Together, they have a far-reaching and sometimes decisive influence on how we function. And not just on digesting food, and keeping the gut and its mucosa healthy. Over the past decade, much research has been done on the relationship between the gut microbiome and the nervous system. And thus the connection between intestinal flora and our mental and emotional well-being. The gut-brain connection, or brain-gut axis, was until recently an unknown phenomenon within science. Grandma's wisdom, about love passing through the stomach, takes on a new dimension.

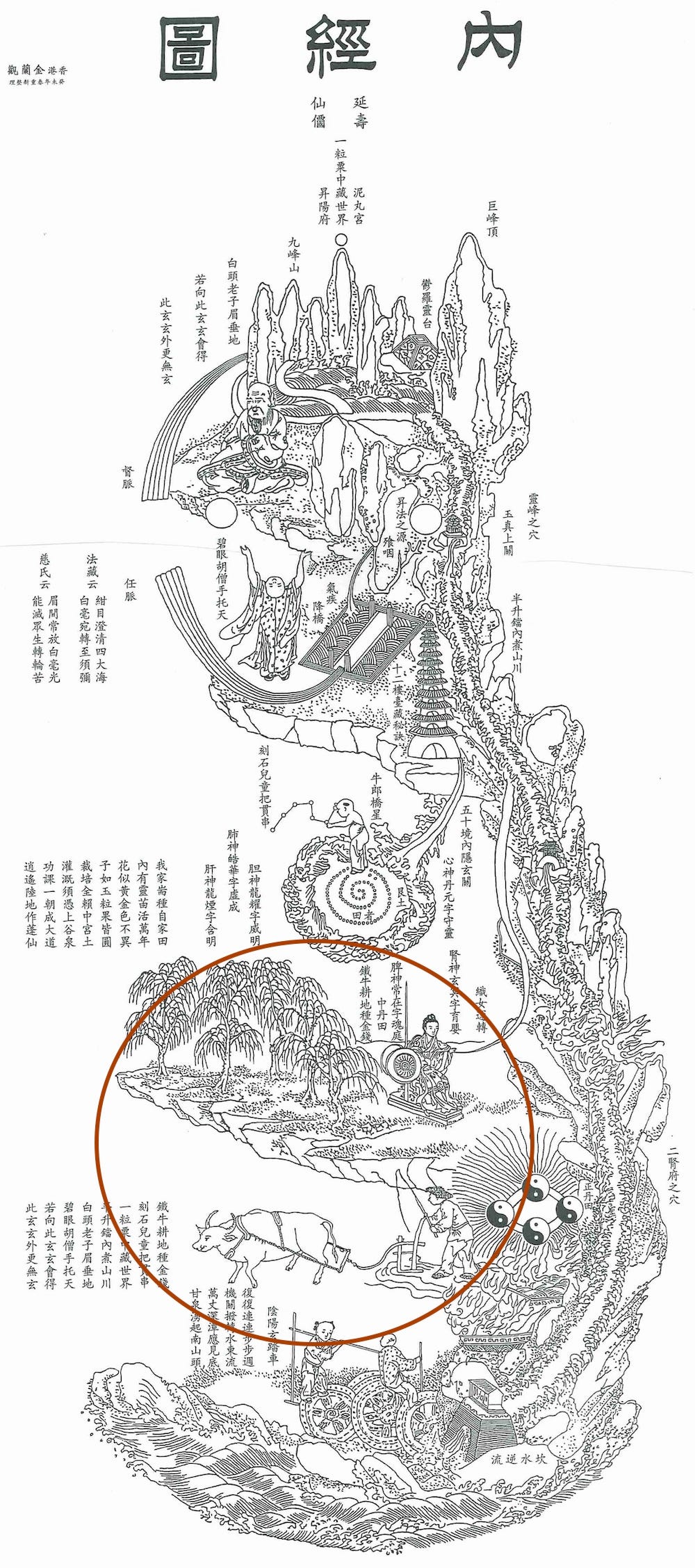

Science is suddenly discovering that a caesarean section birth deprives the baby of essential contact with the mother's microbiome. And that it is actually a good idea for crawling toddlers to put anything and everything in their mouths. And that it is smart (and tasty) to eat fermented food with regularity (read, for example: The Art of Fermentation: Sandor Katz). And coming full circle: the microbiome around plant roots and that in our intestines appear to understand each other. Not unlike an earthworm, which eats its way through its world, we put bits and pieces of our world in our mouths. Chew on it and swallow it. The outside world inside the body. The interwoven mirrored outer world and inner world of the body is the leitmotif of the Nei Jing Tu. In the belly of a seated man: the earth, a ploughing ox, a farmer, and a forest of mulberry trees.

Stand in a natural environment. In a forest, park or in your backyard. Don't close your eyes completely, but give them rest, stand with eyes half closed. Put your hands on top of each other, on your belly. The fingers are slightly spread. Your knees are slightly bent. Don't try too hard to stand 'correctly'. Stand comfortably, not too long, but long enough to become aware of the ground you are standing on. Don't just realise the surface of the ground. Penetrate the earth with your attention. As a plant's roots penetrate the earth. Following the direction of gravity. The dark world you enter is rife with countless larger and smaller and minuscule creatures. Besides the unsurpassed mole and the indispensable earthworm: mites, nematodes, springtails, spiders, centipedes. Besides countless plant roots and hair roots. And an invisible tissue of fungal threads and masses of bacteria and protozoa.

All that life makes noise. Swiss researcher Marcus Maeder listens to the underground with sensors developed for that purpose. In impoverished and eroded soil, it is silent. Regular and intensively cultivated soil apparently has little soil life left. But healthy soil makes itself heard by Maeder. Would that your feet were sensitive enough to do so: while standing, use them as sensors. Listen to the cacophony of micro-sound in the earth!

Now focus your attention on the area under your palms. Shift your attention from the 'big earth', on which you are standing, to the 'little earth' directly under your hands. Here too, food is laid down, broken down, composted, made available. The physicality of this 'little earth' is your ingenious intestines. When stetched out as big as a sizeable allotment. This chi kung pose connects the earth you are standing on, with the earth under both your spread palms. The calm standing chi kung gives your system a parasympathetic boost. Grunting bellies are a well-known phenomenon during class zhan zhuang classes. This stimulus is optimised by a friendly attitude and calm breathing.

HERE OR THERE

In Ted Chiang's short gripping film story The Great Silence, images of the giant Arecibo Observatory in Porto Rico and the surrounding parrot-inhabited rainforest alternate. The observatory watches and listens into infinite space, eventually, hopefully, picking up signals of extraterrestrial life. And one of the parrots narrates.

The humans use Arecibo to look for extraterrestrial intelligence. Their desire to make a connection is so strong that they’ve created an ear capable of hearing across the universe. But I and my fellow parrots are right here. Why aren’t they interested in listening to our voices? We are non-human species capable of communicating with them. Aren’t we exactly what humans are looking for? …

By always looking 'there', we overlook 'here'. In Hidden Life of Trees, forester Peter Wohlleben writes that it is generally accepted that we know less about the sea floor than about the lunar surface. But even less do we know about soil life. What is too close is easily overlooked.

Without going outside, you may know the whole world. Without looking through the window, you may see the ways of heaven. The farther you go, the less you know. Thus the sage knows without traveling; He sees without looking; He works without doing.

Tao Teh Ching chapter 47, translation by Gia Fu Feng

… to be continued