This post has been translated from Dutch into English with DeepL. It will be manually edited and streamlined soon.

The search for the origins of the Eight Brocade Series, the Ba Duan Jin took us to Yu Fei, general of the Southern Song Dynasty. The intervening 900 years have erased many traces of the direct connection between contemporary practice and that in Yu Fei's time. It is therefore not easy to distinguish reality from legend in the story of the Ba Duan Jin's history. Not that that matters much to the contemporary practitioner. A really good story sells itself and continues to be passed on from generation to generation. And the Ba Duan Jin is such a good story.

Every beginning is a continuation of what has proceeded. Yu Fei, too, had his teachers. It cannot have been otherwise, that he based his Hsing I Chuan and his Ba Duan Jin on older sources.

While constructing a hospital in 1971 in a suburb of Changsha, the capital of Hunan province in China, workers stumbled upon what would later become one of the most significant archaeological finds ever. The site of the find was known as Ma Wang Dui, the 'Mound of the Horse King'. Did the hill's name refer to its saddle shape? Or did the name refer to King Ma Yin (馬殷)of the kingdom of Chu (楚)? However, the Horse King was also a deity in the Chinese pantheon: was the hill sometimes dedicated to him at the time?

In 1971, workers in Changsha were digging out a space for a hospital’s air raid shelter in a hilly area called Mawangdui (馬王堆). The work was tough and dangerous, and landslides sometimes interrupted it. The ground felt unstable in one area, so they took a cigarette break before dealing with it, only to find that the sparks from their matches lit up gas seeping from underground. Locals recognised the ghostly blue fireballs as a sign that there was an ancient tomb nearby (decomposing material releases flammable gas), so contacted archaeologists. Under excavation team directors Hou Liang and Zhou Shirong, and with the help of students from local schools, the archaeologists began to carefully excavate the tombs.

So far wonderful ingredients for a Chinese Indiana Jones thrill: an ordinary suburb, a shrine of an old horse-king, a bomb shelter, in the middle of the Cultural Revolution, a smoke break, sparling matches, old tales of blue fireballs.

The archaeologists claim that someone found a leaf deep under the in mud as they were digging. Despite being as old as the tomb itself, it was still green. It was a sign of what was to come. The workers had uncovered the three tombs of Mawangdui. The mistakenly named ‘King Ma’s Mound’ was in fact the Li family’s mound.

Xin Zhui, the marquise beneath the mound - Victor Max Smith

Three tombs from the Han Dynasty were found. The first belonged to Marquis Li Cang ( 利蒼), who had died in 186 BC, but this tomb had unfortunately been looted sometime in history. A second tomb, however, had never been entered and contained an abundance of the most exquisite objects. It had belonged to Li Cang's wife Xin Zhui ( 辛追), the Marquise of Dai. Her body was remarkably intact, lying in four coffins, fitting in each other like matryoshka’s.

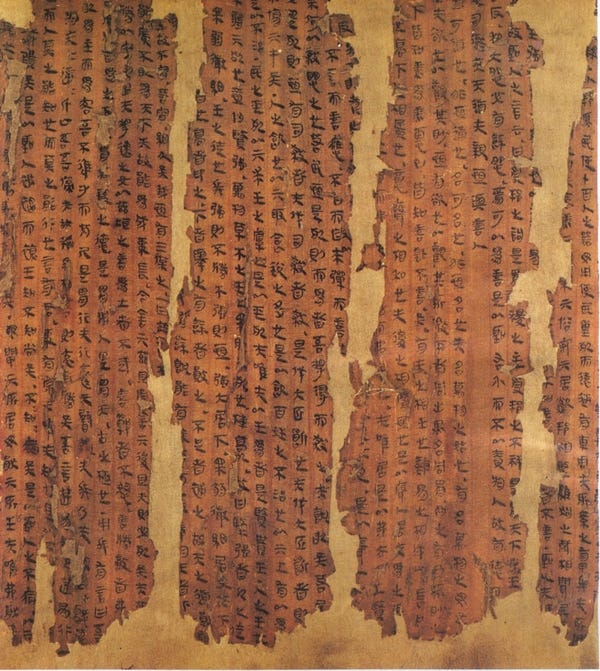

The third grave had belonged to a man who had died young. He was probably the son of the noble couple. The most important find in here was a variety of texts - written on silk, wood and bamboo - including the oldest known versions of the I Ching, the Book of Change and Lao Zi's Tao Teh Ching. The discovery of these texts would give a major boost to the understanding of classical Chinese thought.

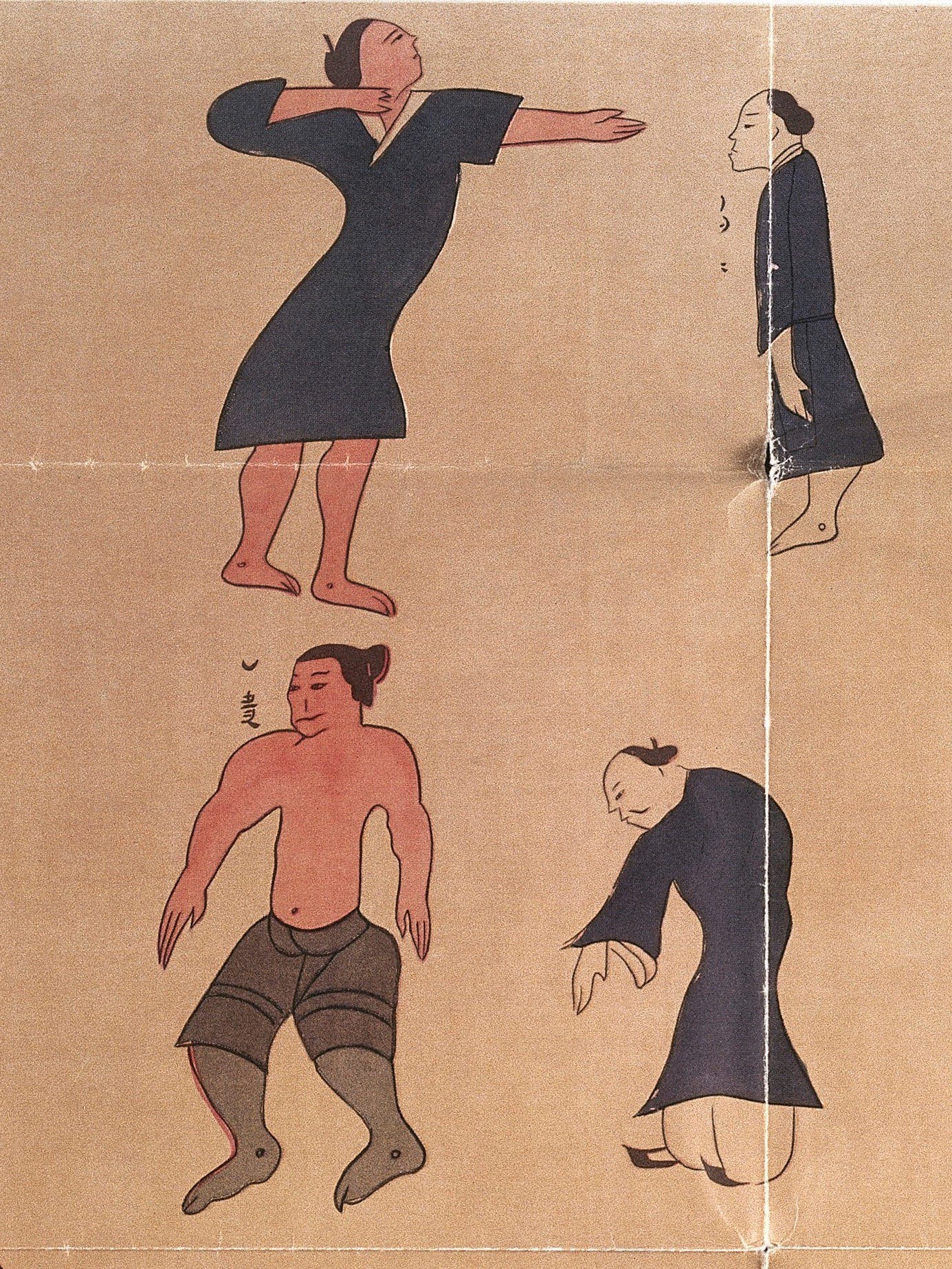

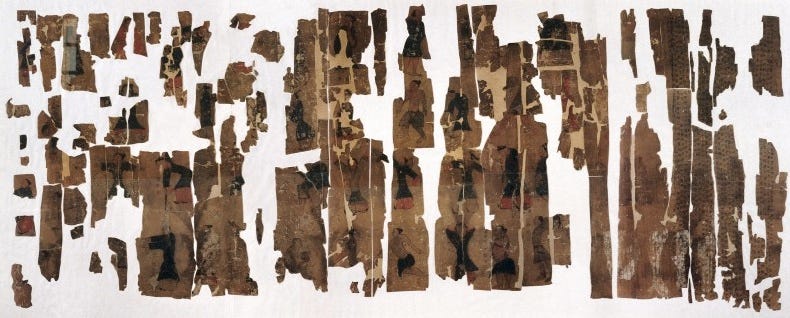

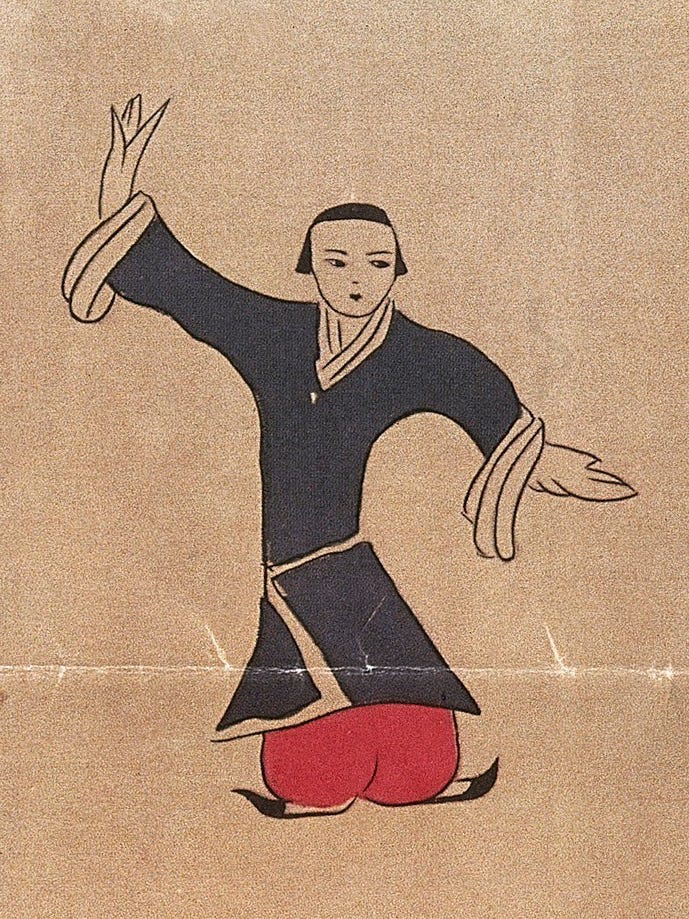

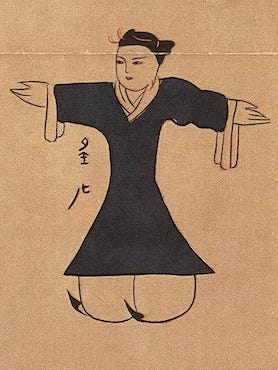

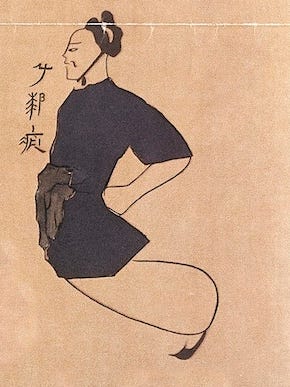

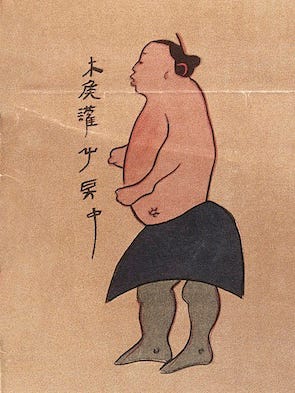

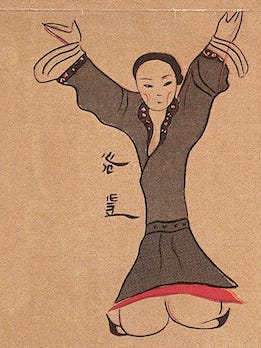

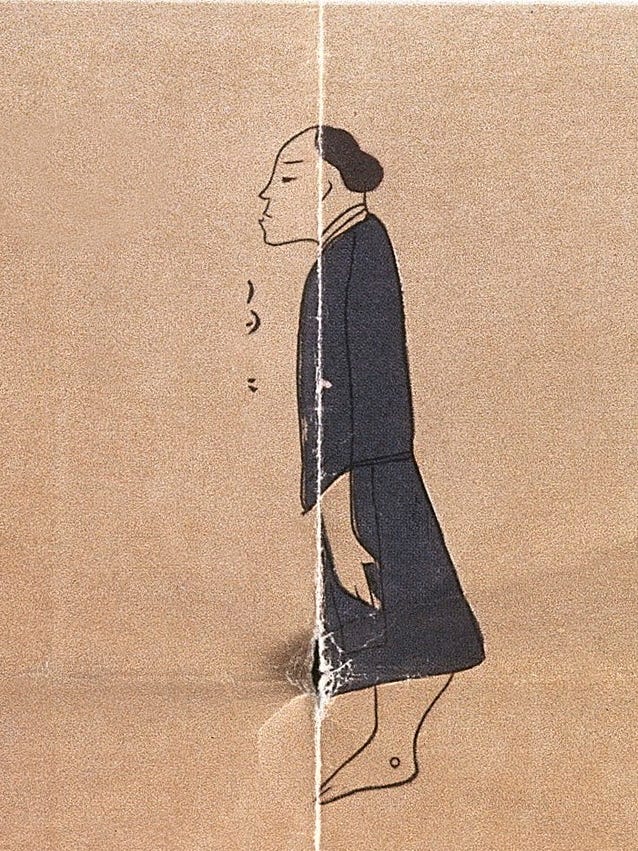

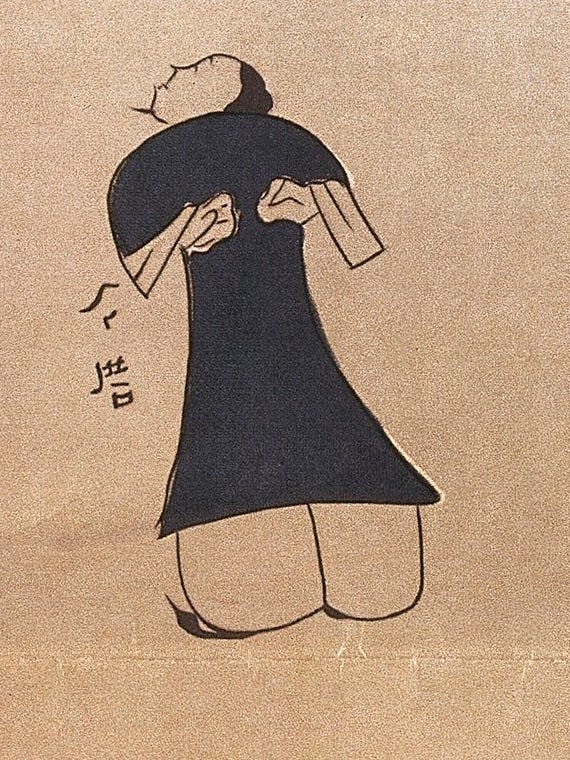

Also found in the younger man's tomb was a painting on silk depicting 44 exercises. This painting later became known as Dao Yin Tu. Dao Yin (導引)is a generic name for a multitude of traditional exercises to improve and maintain health. The meaning of 'dao' (導) is ‘leading’ and that of 'yin' (引) is ‘stretching’ or ‘pulling’. 'Tu' means 'image' or 'map’. The chi is guided into its natural pathways in an interplay of postural training and physical movement, of breathing and aiming through intention. Limbs and torso are stretched, and tensioned and discharged like an arc. Through a combination of techniques that guide the chi and techniques that stretch the meridians, thereby dissolving possible stagnations, chi circulation is promoted.

Large sections of the Dao Yin Tu had decayed and a group of specialists from a variety of disciplines spent a long time considering how the missing sections could be filled. The Dao Yin Tu contains only little text, so that provided little guidance. Furthermore, each illustration is a snapshot of a moving sequence, but it could just as easily be that the illustration depicts a static pose. The final reconstruction of the Dao Yin Tu is marvellous, but how did the researchers arrive at this result, and what choices did they make in the process of reconstruction?

If we take a closer look at the 44 drawn representations and juxtapose what we see with the experience we each have with chi kung, tai chi chuan or any other traditional martial or health discipline, a few things immediately stand out.

The Dao Yin Tu shows both men and women.

Some are barefoot, most are elegantly shod.

Some wear a tunic - common among Han Chinese people - others trousers - in vogue among the northern riding population.

And what kind of people are we dealing with: soldier, acrobat, peasant, civilian?

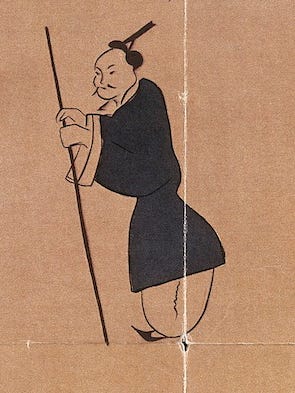

Some figures have bared upper bodies and appear to be engaged in breathing exercises. A few others are practising with a stick.

And does it concern a moving exercise or a standing pose?

And don't some of the drawings resemble parts of the Ba Duan Jin? But the Dao Yin Tu dates from 200-150 BC and according to the historiography, the Ba Duan Jin would only take its form around 1100 AD. How about that?

To be followed up soon ...