HIDDEN TIME. How long can you still lounge before boarding starts? You look around. The large round ceiling clock is encased in a white bag. Nothing to see on it. And further down the departure hall, the other clocks are also enveloped. Strange, precisely at this place, one of Europe's major airports, where the high mass of precise timekeeping is performed. The advent of the train in the late 19th century forced the synchronisation of clocks across the country. Factories and offices brought time further into alignment. Previously, it was lived through reflexive seasons and the rhythm of day and night. It got light, it got dark and in between, somewhere in the middle, the sun was at its highest point. Step by step, the 'approximately' was replaced by 'exactly', which was much needed, because a plane lands here at Schiphol Airport every minute. Punctual.

SCHIPHOL, 29 July 2025. According to the spokesperson, the first clocks were capped back in 2012. 'Because of rising maintenance costs.' The spokesperson could not say what amounts are involved. He did say that it is very complex to keep the clocks running. ... If one of the 87 clocks is stationary, you can't just replace the battery. ...'Repairing the clocks costs money. Replacing them too,' said the spokesperson. 'Covered clocks at an airport, where people still like to know what time it is, are of no use. Schiphol has therefore now decided to remove most of the clocks permanently. 'In places where time is crucial, think transfer zones or gates, they will return. In other places, they will disappear. 'Covered clocks add nothing to the quality and travel experience we want to offer passengers.' nu.nl

LOST TIME. The plane will take you to Milan Malpensa this time. MXP in aeroplane language. No matter where you fly to, every trip is - apart from the destiny airport code - completely interchangeable. The welcome and security chat, the drinks and food, the newspaper or a brief uncomfortable nap. The resolution of the experience of travelling between Amsterdam and Milan is negligibly small. You step out of reality at Schiphol Airport, only to re-enter in Malpensa. As a rule, travelling by plane is smooth, you gain time. Or is the time between take-off and landing just totally wasted, a cut from your life?

'Welcome, please stay seated and still keep your belt fastened', the taxi music, then as fast as it goes through the jet bridge, down the long corridors, briefly going to the toilet, washing hands, perfume cloud from the duty free, luggage belt, customs - you can dream it all, you can go through it with your eyes closed. The time under a copy machine, the boredom. Then the train to Milano Centrale, and if you're lucky, and you are, immediate connection to Genova and La Spezia.

DREAMED TIME. You doze, it was also early rising this morning. The lowlands of Lombardy, the bridge over the Po, your attention flickers. The inexorable sequence of events blends with the cadence and directionality of the train. Wagon follows wagon, like one moment does the previous The arrow-shaped time that - like a needle -threads events together like beads. Without a needle and thread, everything would happen simultaneously. Present, past, future, there and here - everything would happen at once, like emptying a bucket by turning it upside down.

Perhaps you are now dreaming like Zhuang Zhi once did. About a butterfly, fluttering around without any hurry, carefree, knowing that her life will last only a few weeks. Or is it that butterfly, that is dreaming. Dreaming that she is you, nodding off on an Italian train? You open your eyes. Those must be the hills of Liguria.

SCATTERED TIME. After Genova, you are clearer in your head again. The train follows the coast, misty soft light, pastel-coloured villas, vineyards on the slopes. And then, unannounced, a staccato alternation of light and dark. A tunnel followed by views of a wonderful Italian fishing village, followed by another tunnel, and yet another village, even more beautiful than the first. I don't know if you know, this is iconic Italy, the Cinque Terra, at the top of every self-respecting bullet list. You must have been here to experience the tranquillity and authentic life. During the half-minute - the interval between two tunnels - you have a good view of yet another village and the crowds of tourists in the narrow streets and around the small harbour. On the paths connecting the Cinque Terra villages, there are regular traffic jams. Of travellers, of vacationers, of seekers of emptiness. There are time slots for walking from one village to another, and everything you would have liked to do spontaneously has to be booked long in advance. Surely, the etymology of 'holiday' must really be sought in the notion of emptiness. Emptiness of worries and emptiness of time pressure. Anyway, these dilemmas have nothing to do with you now.

BORROWED TIME. In La Spezia, you have an hour. It is now late afternoon and the train to Aulla will leave a bit later. Outside the station you find a small park. And what suits you nicely, there is a free bench. The dull rhythm of airport, plane, station and train is still under your skin, and how good it is to simply sit and look around. You don't know anyone here, no one knows you, you have no obligation, and the train to travel on is not here yet. Was it long ago that you had nothing to worry about and didn't get nervous about that? Was it long since you could observe freely? There to your left, an old man approaches, shuffling along. A friendly old gentleman, grey, slightly stooped. For a moment freed from the compulsive restlessness of doing, you can see beyond the limitation of the single moment. You see today's old man and you see the young fellow he was yesterday. Why creating separations and denying the one the naughty pranks and dreams and the other the wisdom? You see young in old and old in young.

ELAPSED TIME. In Aulla, a small nondescript town in the Magra valley, you are picked up. A vital, tanned man is waiting for you outside the station, leaning against a jeep, that has clearly been through a lot. He introduces himself to you: no, he is not Italian, but actually he is. Originally from Switzerland, he has lived here most of his life. You hit the road and that road leaves the sleepy town, into the hills. Your driver seems to be able to dream the route and does not skimp on speed. There is nothing to do but trust his steering.

If you look from the side at his hands, which loosely encompass the steering wheel, it is clear that they have been doing labor. And if your eyes discretely wander down, you see that he is driving a car with no shoes on. When he notices your searching eyes, he smiles. 'The other day I was stopped, routine check, by the carabinieri. I don't think they had experienced that before, a barefoot driver. 'That's not allowed, signore, please, shoes on behind the wheel.’ I complied, but you just drive much better without them, you have much more feeling with the car.'

Meanwhile, you drive through wooded hills, here and there a village, a group of talking people, a river, a bridge, trees, trees everywhere. 'Yes', he says, 'earlier, longer ago, this region was much more inhabited. Like in so many places in the world, families migrated to the city. In the village where we live, it is quiet in winter, there are few of us living there. Yes, in summer, then they come, from the city, to the family house. Ferragosto, the holiday. And as soon as it ends, back to the city. Their heart is here, but yes, there is nothing to earn.'

The jeep turns a corner, the narrow valley widens and a wide view presents itself. In the distance, steep slopes rise out of the green hills. The peaks turn soft red by the light of the early evening. 'Those are the peaks of the Apuani’, he says, ‘you can't see it from here, but on the other side, just below the summit, are the marble quarries. Michelangelo got the white marble there, for his David, and other of his works. In a straight line it's not far, Carrara, Massa, that's where the money is made. That marble is shipped everywhere. This here is another world, the mountains are in between. This land is called the Lunigiana, the land of the moon. It was always a forgotten part of the wealthy Toscana, and in fact it still is. Look there’, and he points ahead, towards a wooded slope, ‘there were terraces there not long ago, barley and vegetables, fruit trees. The Lunigiana emptied in the last century and the fields and villages depopulated.'

We drive on for some time without talking. The road gets narrower and even more winding. The evening sun is no longer able to peep over the hills. The green becomes dark green. 'Look', he says, making a broad gesture from left to right. 'Chestnuts, all chestnuts. The whole region is covered with chestnut forest, planted long ago. That used to be an important part of life for the people here. In autumn, chestnuts were collected, and dried. Chestnut flour, chestnut bread, chestnut biscuits. Yes, it is still done, but not on the scale of back then. What did they have? Wild boar, chestnuts and porcini. Many of the chestnut plots were abandoned, and rewilded. You'll see tomorrow.'

Dusk has set in. The winding road and your empty stomach don’t combine well together. Then your driver says: ‘there it is, that's Casola.’ You see a medieval village, glued against a hillside. And there lies Il Convento.

The jeep turns right into a dusty path, which after a short time is crossed by a small river. The driver does not hesitate and steers the jeep through the splashing water. A sharp turn and then steep uphill and we stop in front of the old monastery. He switches off the engine, we open the doors, get out, the engine hums and ticks. It is silent.

TWISTED TIME. Throughout history, in all cultures, trees held a special place and it is no different today. Yes, yes, surely you mean in the form of lumber and Christmas tree plantations? Ireland and Portugal were covered in oak forest, all of Europe was once one big forest, and look at it now. And just signing petitions to save the forests in the Amazon and Borneo, while here the continent was stripped of its trees long ago. Of course, there are forests allowed on this continent, as long as the trees stand nicely in rows next to each other and quickly provide straight lumber.

Our society worships youth. Fresh cheeks, tight body, youthful attractiveness. Everything possible is done to avoid wrinkles and, above all, to preserve the body as untouched as possible. Imagine what it would be like: on all billboards, in TV advertising, old wrinkled faces and aged bodies displayed to advertise products. It could be reality, in a distant future, old age and weathered bodies as an ideal to be pursued.

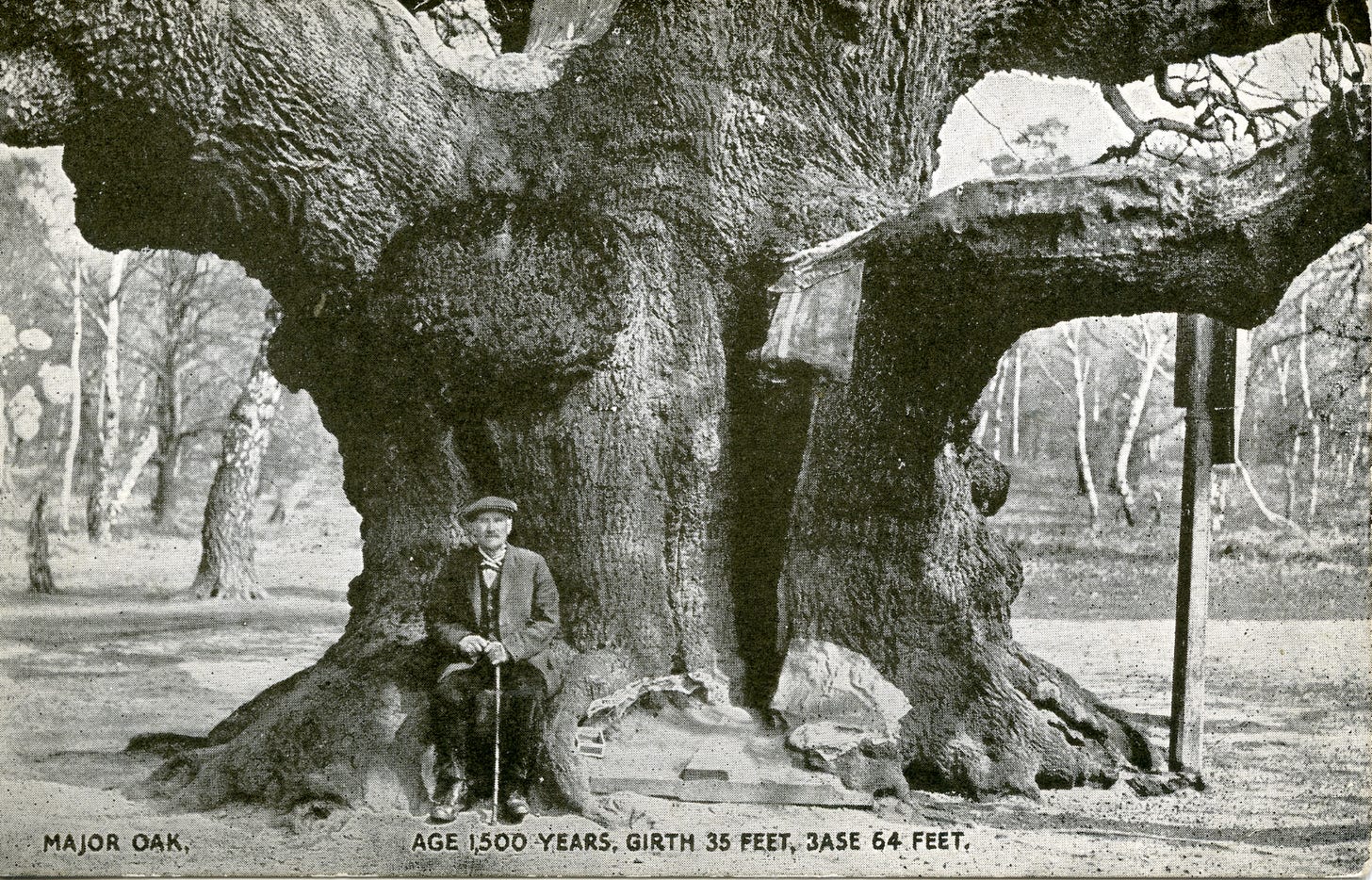

That is exactaly how we observe trees. An ancient lime tree, a rare old specimen, a fence around it, a placard with his history and what he has witnessed. That tree as a curiosity. In regards to trees it is all about old age, weathering, twistedness. Tell me, you wouldn't go to all the trouble, make a long diversions to go and look at a youthful spindle, straight and lean, with soft flawless skin, and translucent leaves.

How can you become as old as that linden? Definitely not by standing out much, or by trying to be useful.

Carpenter Shi went to Qi and, when he got to Crooked Shaft, he saw a serrate oak standing by the village shrine. It was broad enough to shelter several thousand oxen and measured a hundred spans around, towering above the hills. The lowest branches were eighty feet from the ground, and a dozen or so of them could have been made into boats.

There were so many sightseers that the place looked like a fair, but the carpenter didn’t even glance around and went on his way without stopping. His apprentice stood staring for a long time and then ran after Carpenter Shi and said, ‘Since I first took up my ax and followed you, Master, I have never seen timber as beautiful as this. But you don’t even bother to look, and go right on without stopping. Why is that?’

’Forget it—say no more!’ said the carpenter. ‘It’s a worthless tree! Make boats out of it and they’d sink; make coffins and they’d rot in no time; make vessels and they’d break at once. Use it for doors and it would sweat sap like pine; use it for posts and the worms would eat them up. It’s not a timber tree—there’s nothing it can be used for. That’s how it got to be that old!’

After Carpenter Shi had returned home, the oak tree appeared to him in a dream and said, ‘What are you comparing me with? Are you comparing me with those useful trees? The cherry apple, the pear, the orange, the citron, the rest of those fructiferous trees and shrubs—as soon as their fruit is ripe, they are torn apart and subjected to abuse. Their big limbs are broken off, their little limbs are yanked around. Their utility makes life miserable for them, and so they don’t get to finish out the years Heaven gave them, but are cut off in mid-journey. They bring it on themselves—the pulling and tearing of the common mob. And it’s the same way with all other things.’

‘As for me, I’ve been trying a long time to be of no use, and though I almost died, I’ve finally got it. This is of great use to me. If I had been of some use, would I ever have grown this large? Moreover you and I are both of us things. What’s the point of this—things condemning things? You, a worthless man about to die—how do you know I’m a worthless tree?’

When Carpenter Shi woke up, he reported his dream. His apprentice said, ‘If it’s so intent on being of no use, what’s it doing there at the village shrine?’

‘Shhh! Say no more! It’s only resting there. If we carp and criticize, it will merely conclude that we don’t understand it. Even if it weren’t at the shrine, do you suppose it would be cut down? It protects itself in a different way from ordinary people. If you try to judge it by conventional standards, you’ll be way off!’

Zhuang Zi - translation by Burton Watson

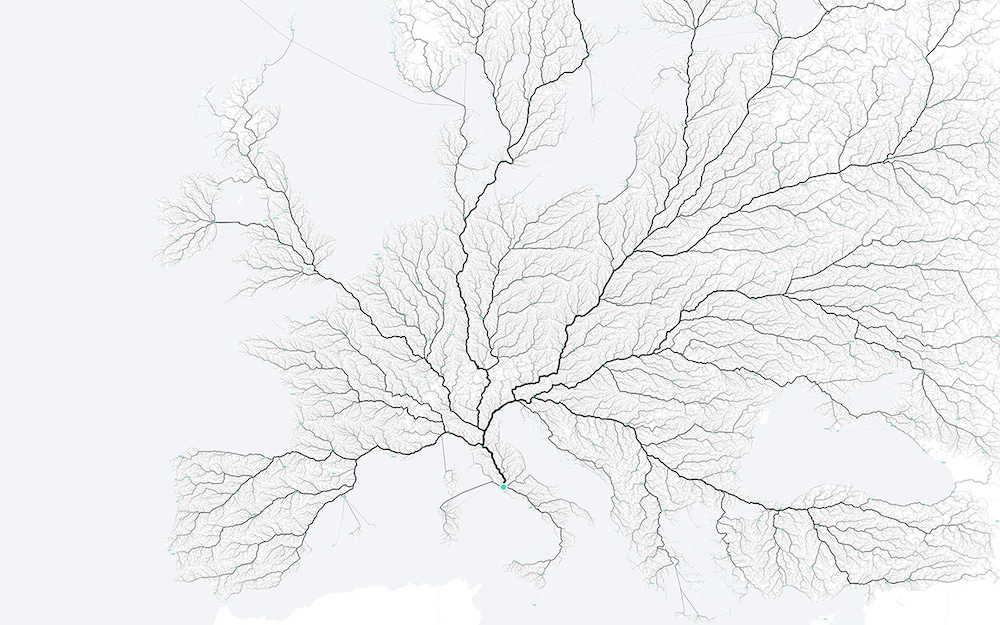

TIME LINE. You wake up early. Everything in this monastery breathes history. The robust stone walls, the ruins of what was once a chapel, the pavement of the forecourt. You don't know it, so I whisper it in your ear: this was once a refuge for pilgrims on the road to Rome. Sure enough, all roads lead there, and the closer you get to the eternal city, the more all those roads have come together, like the tiny veins converge in the large central vein of a leaf.

UNSPECIFIED TIME. This morning at breakfast, you met the wife of yesterday's jeep driver. The latter, incidentally, turned out to be the owner of the old monastery. Found as a ruin and rebuilt into what it is today. Ah, that's where the penny drops - those working hands, you had noticed them during the drive. And so this woman is the owner as well. Her gaze is intense, her appearance earthy. 'I wasn't born here either,' she told me, but by now I belong here. I ended up in Italy at the time, by chance, in Pontremoli, as a member of a theatre group. Do you know Pontremoli? It's not far from here, also in the Lunigiana. Inside the castle, steles are on display. Strange, intriguing statues from prehistoric times, all excavated around here. That's how long the Lunigiana has been inhabited.

Deciding to stay here, we drove through the Lunigiana, without a defined plan, looking for a place to settle down. As if by chance, we found the Convento. Half in ruins and completely overgrown. We took a walk around the area, came into the old chestnut forest and that made it all clear. This was without a doubt the right place to stay.'

‘To get into the old chestnut forest, you also have to know where to enter. In the past, when this whole area was more populated, there were countless paths running through the woods, over the hills, from village to village. Paths used by porcini pickers in autumn, and chestnut gatherers. Now, if you walk into the forest, randomly, just from somewhere along the road, you won’t come far. Brambles, prickly plants, tough bushes, there is no way through. Go there and have a look. I can't go with you myself today, but my children are here and can show you the way.'

Just as Harry Potter had go to King's Cross, platform nine three-quarters, where he had to pass a wall in a rather unusual way, all in order to travel to Hogwarts, the entrance to the ancient forest is located at an unexpected place.

FORGOTTEN TIME. In the stone wall that surrounds the monastery you find the door, colourless and inconspicuous. The two young people are already there waiting for you. The door opens with some creaking and squeaking and you are standing on a narrow forest path. That path follows the outside of the monastery and then dives into the dense foliage of the forest. When you turn around after walking for a while, you see the hushed village in the distance. The sounds of the world - a power saw, the knock of a hammer, a crying child - fade away and are absorbed by the silence.

At a fork in the path - you would have walked right past it - the young man says: ‘straight ahead it continues to the convent of Codiponte, we turn right here.’ Near the fork is a huge chestnut, with a hollow base, from which a large number of stems have grown. You remain standing, is it your imagination? Looking through your lashes, it seems a forest spirit, with a tangled bunch of hair, a wild beard and open mouth, a silent scream. An ent from the Lord of the Rings, Treebeard. Is this the guard at the entrance to the ancient forest? No, your fantasy is to vivid. Still, you don't dare take a picture of this bizarre apparition. The two young people have moved on and you now walk a little faster to catch up. They certainly haven’t notice anything about your imagined encounter with the old tree.

For a few more minutes, you walk on. The conversation is hushed. I know, the atmosphere of the place where you stop is hard to describe, so I won't try. The three of you sit with your backs against the trunk of one of the forest masters. The sun can barely penetrate the thick foliage, the light is dappled and green. This time is the time of the trees. How long you sat there?

On the way back, as you pass the guard, you give a hidden nod of your head, as a sign of respect, After all, you never know. But the young woman saw your furtive gesture, your gazes cross. She smiles and winks. Would she know the guard too?

As you approach Il Convento again, you pick up the conversation again, at the same point where it had died down on the way out.

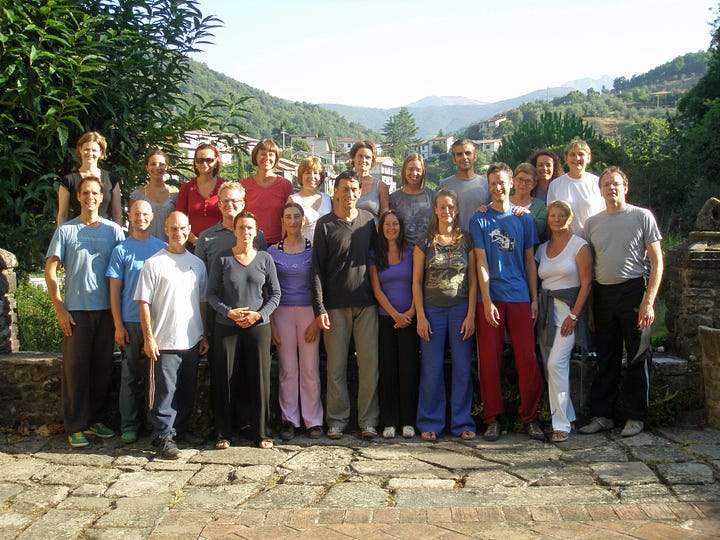

THE TIME GONE BY. Now that I have retold your journey, or inspired you to make it soon, we can talk further. I know the road that starts at Aulla well. I remember the hundred curves up to the small medieval village. And the first night's stay at Il Convento. That was 1999. The following morning we took a walk and - was it a coincidence, was it the magic of the wooden door - we found the ancient forest. We sat leaning against an aged chestnut tree, silently, was it an hour, was it longer? It was clear, this was the right place to organise an annual chi kung summer school. The first one in 2000 and about 15 more would follow in the years after.

TREE TIME. Participants came from all directions: Iceland, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, England, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Poland, Spain, Portugal, Austria, Switzerland, America, Italy and, of course, the Netherlands. At least once during each summer school, in the afternoon, once the heat of the Italian summer had calmed down a bit, we gathered at the wooden door in the outer wall of the monastery. Squeak open, everyone through, squeak shut again. Gaily chatting, we then followed the same narrow path on which you, with Shirin and Aaron, the two young people, walked. At the level of the fork and the guard, the carefree chatter had invariably lost its volume, and when we finally reached the oldest part of the chestnut grove, it had fallen completely silent. Not because it was so agreed - we were probably absorbed into the time scale peculiar to trees. Talking then becomes more laborious, actually redundant. Tree time, exactly, that the right term.

For some, chi kung practice in the ancient chestnut forest consisted of sitting simply, with their backs against a tree. Others lay down for a moment on the soft ground and fell into a deep sleep. And there were, of course, some who practiced chi kung in a more recognizable form. But all experienced a naturalness, an effortlessness. Like when it rains and you don't have to make an effort to get wet. Being present is enough.

TIMELESS. Shirin and Aaron's parents, Martina Weber and Marcel Müller, who have rebuilt the Convento over the years at an unruffled pace, provided warm hospitality year after year. They offered the perfect conditions for intense chi kung study. The first time I visited them, their children were small. Now they are adults and the initiators of a recurring summer festival in and around Il Convento.