This is a revision of the first part of Chapter 1 of The Dynamics of Standing Still.

Transport your thoughts to the origin of existence, to the beginning of the unimaginably long process of evolution. The very first life forms consisted of a single cell, without a central nucleus. Single-celled organisms with a nucleus would not appear until two billion years later. A tiny lump of life, surrounded by a wafer-thin membrane, separating and connecting the outside world and the inside world, and in the middle a nucleus.

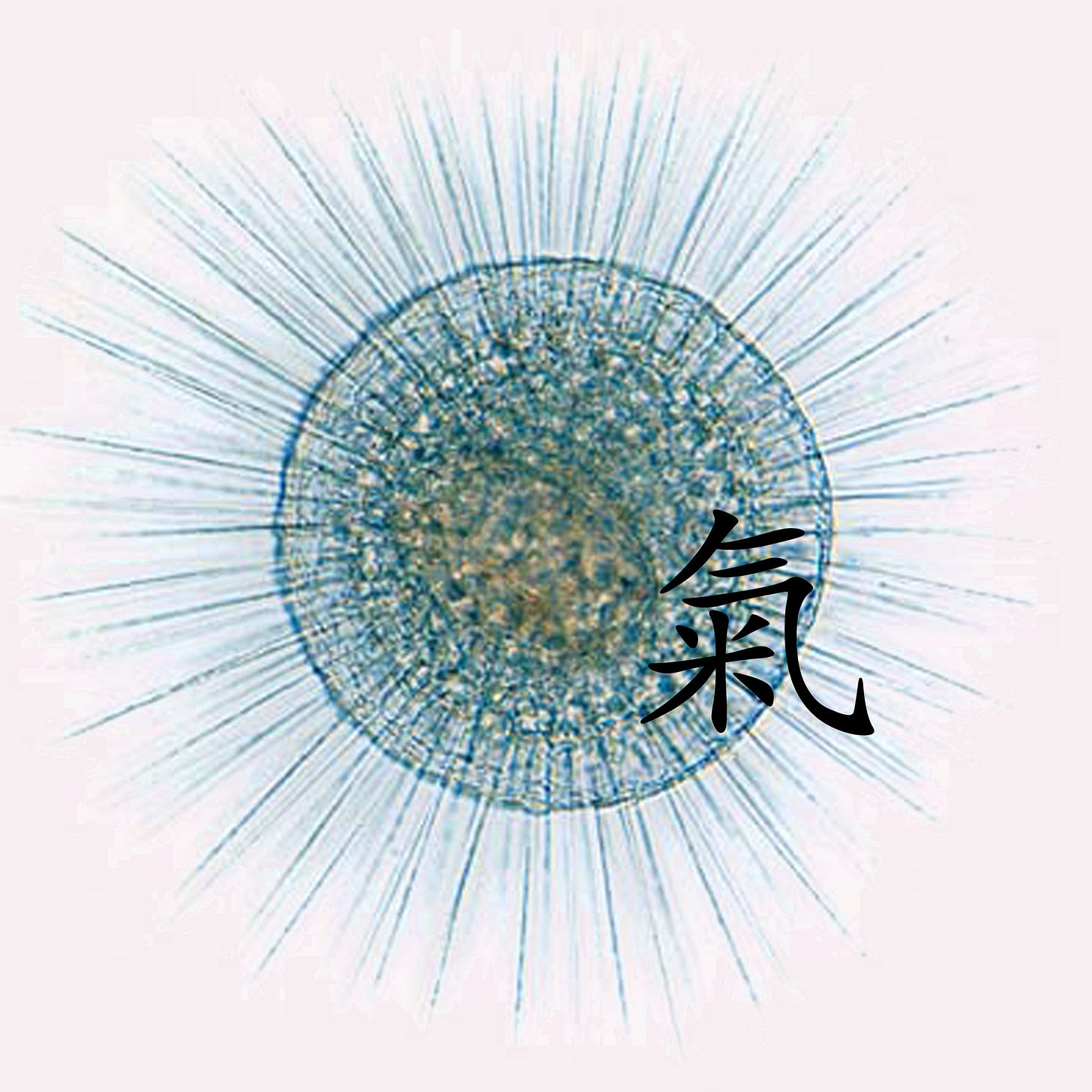

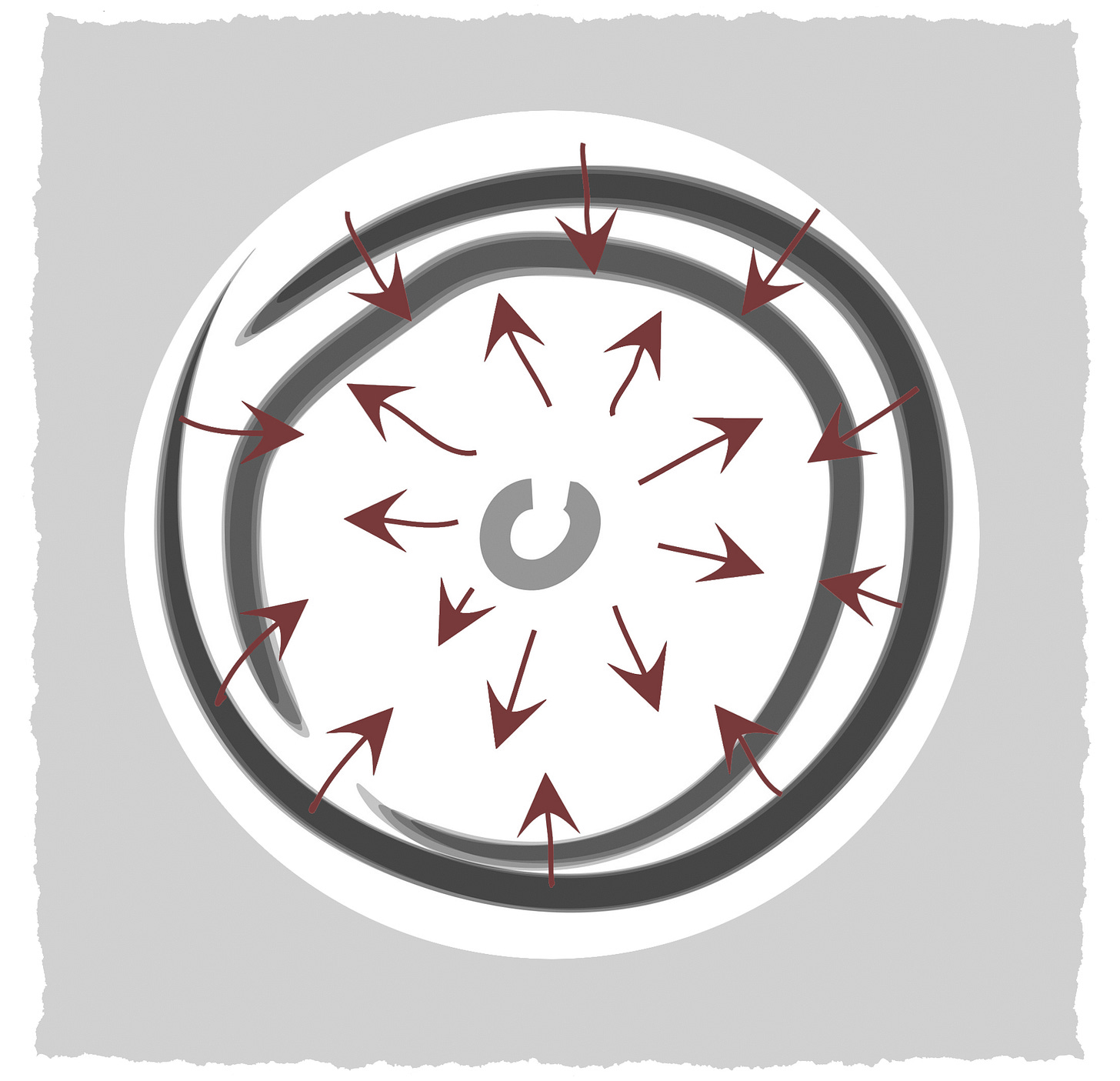

While Western medical and biological sciences investigated the material and biochemical properties of cells in order to shed light on the mystery of life, Eastern empirical science focused on a fundamental life function found in all living beings: pulsation. It is the rhythmic alternation of tension and relaxation, of contraction and expansion, the succession of inhalation and exhalation, the dynamic ability to adapt to ever-changing environments and circumstances. Pulsation can be found in all their body parts, all their organs, tissues and cells.

The fundamental phenomenon of pulsation is captured by the Chinese character chi, 氣. Without chi, matter is lifeless. Without matter, chi cannot manifest itself.

Chi is the central theme in Chinese natural sciences, traditional medicine and martial traditions. Developing sensitivity to chi is a prerequisite for every practitioner of the aforementioned disciplines. But where to focus? Develop sensitivity to what? As a student, one may have the misconception that chi is an extraordinary quality, a mystical property that can only be perceived with a special sensitivity. The reality is simpler.

When a party, a training course or a public transport network is organised in an exemplary manner, this largely escapes the notice of those who is involved in it. Good organisation seems self-evident. A well-functioning liver or healthy teeth do not attract attention, and in such cases it is quite normal to be barely aware of their existence and flawless functioning. Only when the chi is blocked, only when the level of chi is low, and this manifests itself as pain, fatigue or discomfort, does it become apparent to the consciousness. Chi is therefore not a mysterious quality. It is the background noise of well-being. To perceive chi, one need look no further than everyday life.

For the Groote Museum in Amsterdam, we produced a film showing the many forms of pulsation and rhythm: circadian rhythm, the transformations of the seasons, birth and death, heart rhythm, breath-pulse... The film can be seen within the ‘circularity’ installation.

From a single-celled organism to a sea anemone is a giant evolutionary leap. The complexity of an anemone or jellyfish is incomparable to that of microscopic pioneers of life. What remained the same, however, is the unambiguous rhythm, the archaic pulsation.

As single-celled microorganisms evolved, they grew larger. Having a centralised organisation was no longer enough to withstand the challenges and dangers of the environment. The larger whole was split into smaller parts, each with a degree of autonomy.

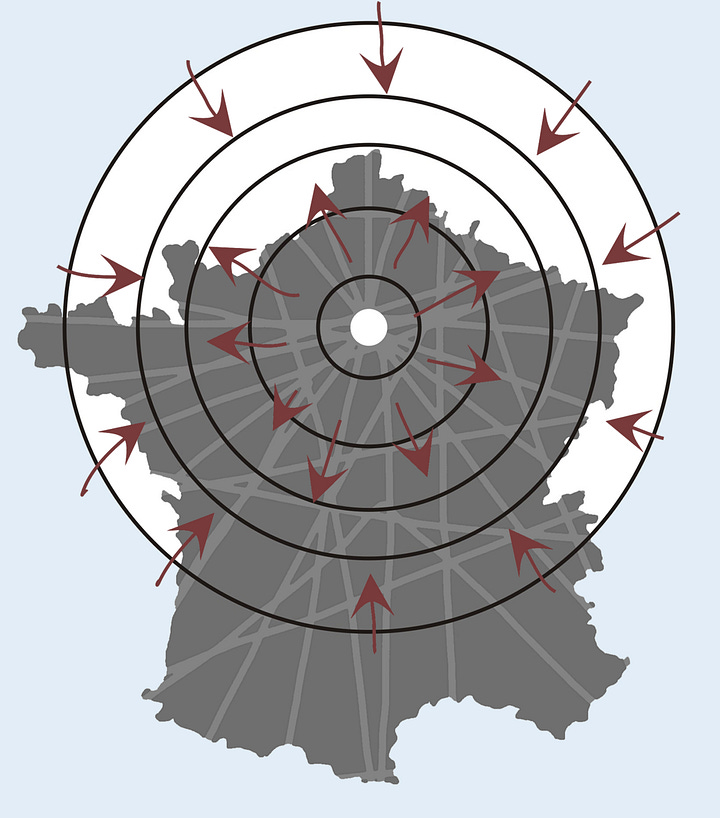

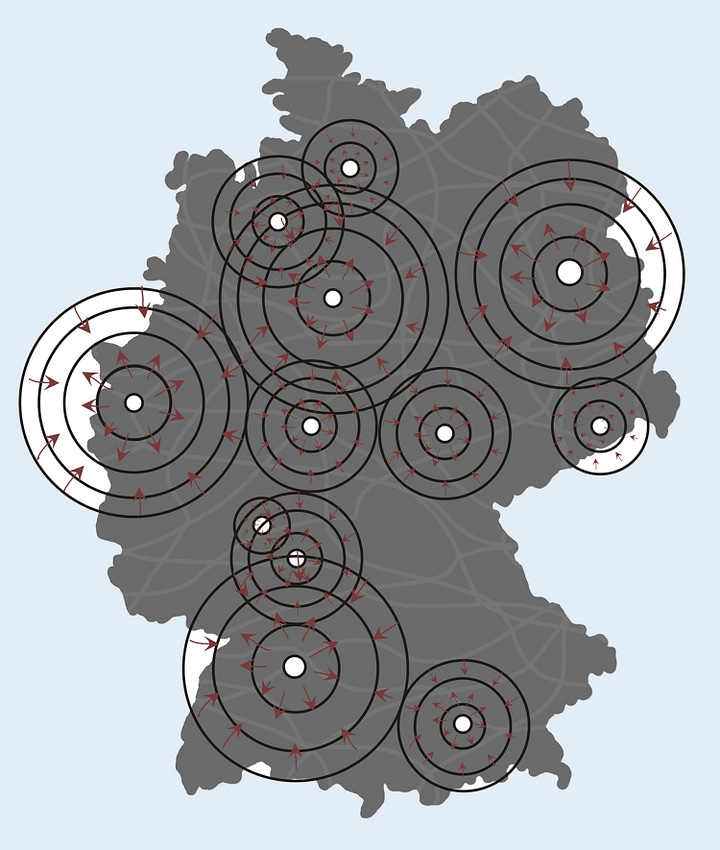

A large country with a single central capital can easily take concerted action when circumstances require it. For a decentralised country, this is not a given. It takes time and tact to get everyone on the same page. On the other hand, local autonomy leads to greater sensitivity and a more finely tuned ability to adapt.

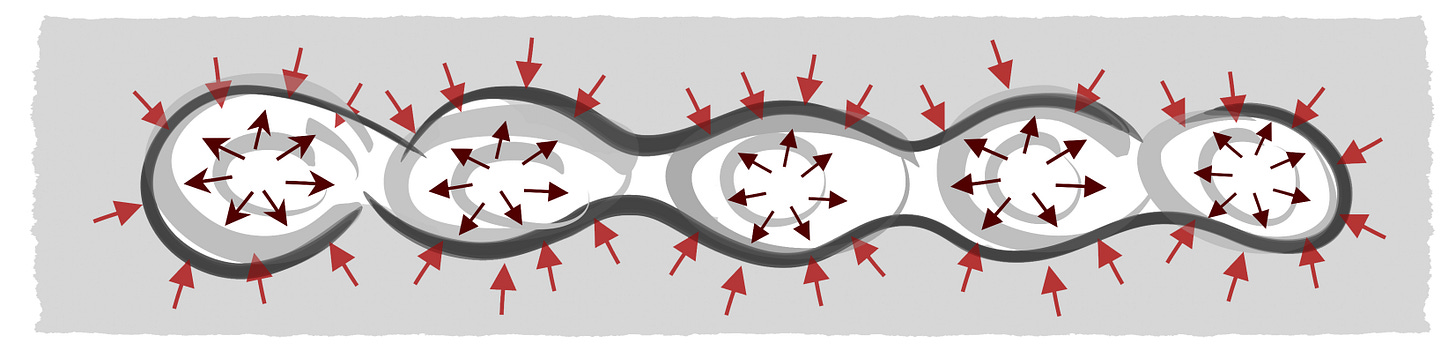

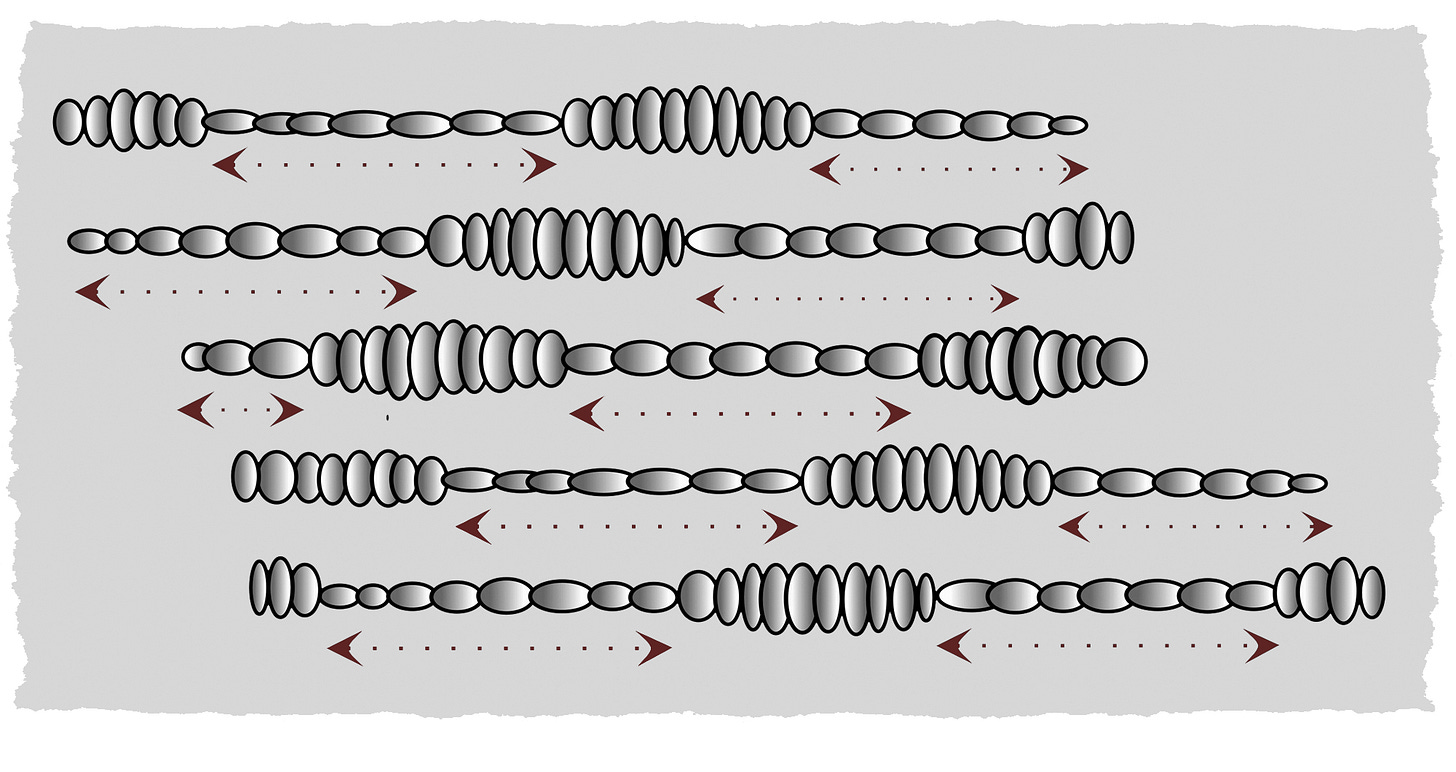

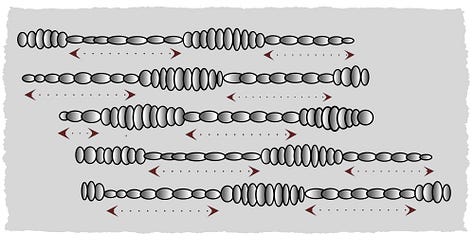

An earthworm exhibits a combination of both. Its body consists of a multitude of virtually identical segments, each pulsating around a local centre. An orchestration creates an accordion-like movement of the whole, a rhythmic interplay of all parts.

The segments of the earthworm, or metameres, are separated from each other by thin connecting pieces called septa. These separations enable the segments to pulsate individually and, from there, to produce a collective peristaltic movement.

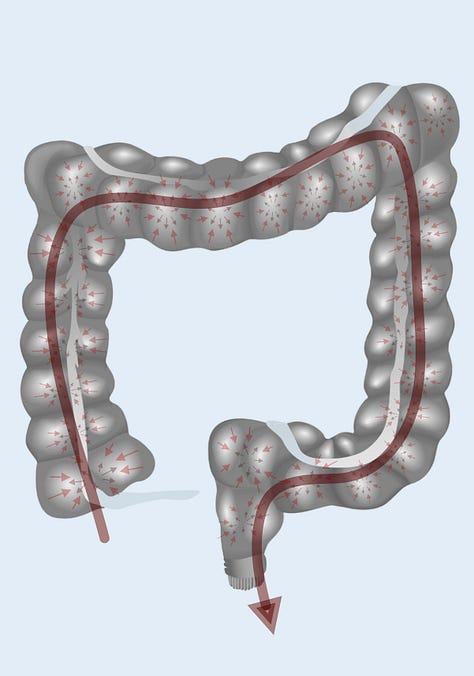

The septa are permeable to bodily fluids, blood, nerve pathways and the long intestinal system. The latter bears a strong resemblance to the external form of the earthworm. Pulsation of one propels it through its environment – which is also its food source. Pulsation of the other propels that same environment – or more precisely, the part that serves as its food – through it.

Two in one. An outer worm and an inner one hidden inside.

At the front of an earthworm’s body is its mouth. This guides the body’s crawling movement through the soil, which it leaves ploughed. The same mouth allows soil into its intestines, which is then digested and excreted through its anus, located in the very last segment.

For the ‘You are what you eat’ exhibition at the Groote Museum in Amsterdam, we gave the earthworm the leading role. Described by Charles Darwin as a natural plough, the earthworm plays an essential role in soil fertility.

to be continued …